First, a little housekeeping: I last wrote almost two years(!) ago, and since then, I’ve moved this email list to Substack. I’ll be shooting to send out monthly notes on books I’m reading. This is a year-in-review style essay covering all of 2022.

1.

This year, I built a levee of books around me, a wall meant to hold back the rising panic that builds once a week or more these days: what, exactly, did you accomplish today?

Reading is a joy, yes. It’s also my last, best defense against the cold waters of instrumentalism, a logic that demands I measure my life only with the crude yardstick of the things I produce. But reading certain magical kinds of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry refutes that logic, because, unlike nearly every other one of my activities, reading captures my full attention while accomplishing more-or-less nothing measurable except the passage of time.

At work, I produce—if I can be immodest for a moment—a lot of things. Many of them are even good things. In measuring my time at work, I try to pick a useful metric. Not just, say, lines of code I’ve written, but the quality of facts that my code has uncovered. It works, most of the time. But if I think my life is full because I produce measurable things, I end up with a lot of things and very little life.

So, reading. Ink on paper. The weight of a book. Time spent with body and breath, my mind both present and not. The moment when, chapter finished, I lift my head and sigh and am in the world once again and everything and nothing has changed.

The miraculous thing about reading is that while the act itself is measurable, its impact is not. It defies instrumentalism, and, unlike the rest of life, I have never presumed it could fit into the inhuman logic of productivity.

I read, so far this year, 100 books. I read academic nonfiction (dark green), science fiction (light green), literary fiction (light blue) and nonfiction (dark blue), poetry (gold), romance (yellow), and upmarket fiction (purple). Some books I loved. A couple I abandoned. Nearly all fit into the broad middle of definitely worth reading but not totally revelatory.

Here’s a chart of books I read, ordered by when I read it, sized by my subjective experience of its ambition and execution. The taller the book, the more ambitious and/or well-executed I found it.

2.

In May, I read almost exclusively romance novels. While I loved many of them as individual books (Mhairi McFarlane’s Don’t You Forget About Me and Beth O’Leary’s The Flatshare are real standouts), this year, it was the experience of reading so much romance in aggregate that changed my perspective on literature the most.

At times, I have felt ashamed that a little under half of the books I read were romance, but I know that this shame is misplaced. It’s not that some books aren’t more worthwhile than others. It’s that the source of a book’s worth is not its genre—its markers of seriousness or its relevance to some tired definition of “the human condition” (or whatever). A romance, when taken as a piece of art just as worthy of reflection as any other piece of art, can rise above or fall flat, just as the latest book of literary fiction can.

In fact, I think it’s a species of instrumentalism to view genre as the site of artistic goodness. The author Garth Greenwell writes in Harper’s about the foundations of the “brutal calculus” that readers often bring to bear on their reading lists: “resources are finite; time is finite; every book exists at the expense of another; any book I read represents a different book I could have read instead.”

I understand wanting to read books you will find meaningful and not books you won’t find meaningful, but why should genre be the locus of that meaning? I contend that genre is often a cruel shorthand, a way of devaluing books that don’t signal seriousness—not, in fact, an indictment of a book’s meaningfulness.

But, no: I don’t propose that you ought to read more romance. I do propose that you read from a place of abundance and not from a place of scarcity. Greenwell continues: “Maybe what I’m suggesting is pure fantasy, imagining that our attention could be like the loaves and fishes at the feeding of the five thousand. Maybe that’s true. But maybe it’s also true that there are certain indefensible positions we must hold because not to hold them would be an affront to the human dignity necessary for any world in which we should rightly wish to live.”

If you are not swayed by this appeal, then consider this. Gabrielle Zevin’s Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow, an undoubtedly (let me adjust my tie here) literary book, is also a romance. Same for Sarah Baume’s Seven Steeples. They don’t adhere quite as closely to the tropes of romance fiction as many of the books I colored pink, but they are romance in a meaningful way nonetheless. Both these books I found utterly sublime.

3.

Speaking of romance, I had the joy of reading Anne Carson’s translation of Sappho—If Not, Winter—and Mary Barnard’s older translation—Sappho: a New Translation—back-to-back. Since I’m a sucker for covers, and since I’m unfortunately monolingual, this kind of translation-to-translation comparison is the closest I can really get to one of my favorite pastimes: listening to a song, then listening to every cover I can find.

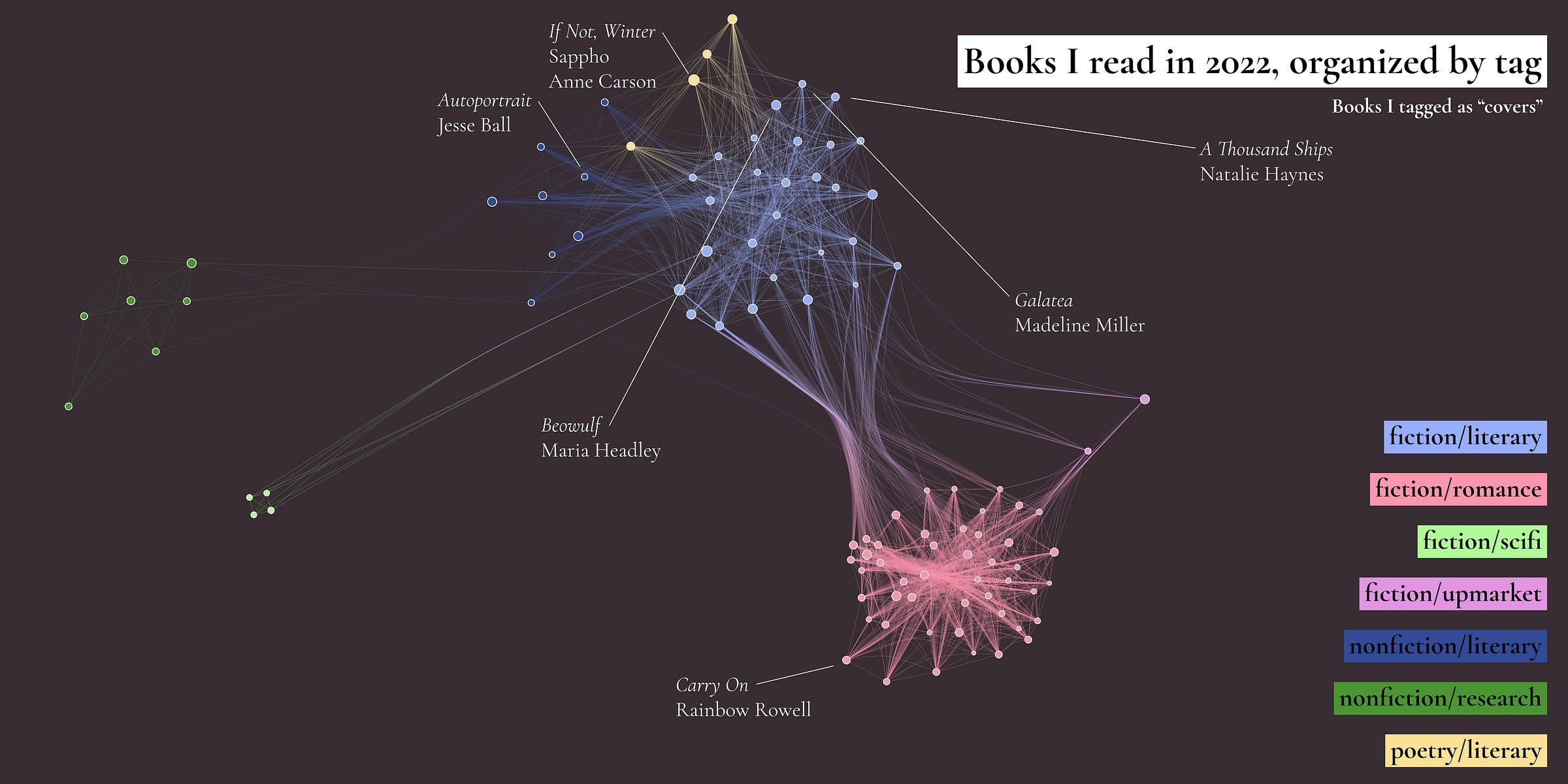

These weren’t the only covers I read. Here is a network graph of books I read, where books I tagged in similar ways are pulled close together, and books I tagged in dissimilar ways are pushed far apart. I've labelled the covers. Most, like Carson’s If Not, Winter (Sappho), Natalie Haynes’s A Thousand Ships (the sack of Troy), Madeline Miller’s Galatea (one of Ovid many metamorpheses), and Maria Headley’s Beowulf (Beowulf) are covers of ancient stories. But Jesse Ball covers Édouard Levé’s early-aughts book of the same name. (Chelsea Hodson’s cover of Levé is my personal favorite of that very small subgenre), and Rainbow Rowell’s Carry On is a surprisingly moving reimagining of a Harry Potter-ish universe.

The wonderful thing about covers is that you can really see which parts of a familiar story an author wants to engage with, and which parts she wants to set aside. Anne Carson is always able to bring something fresh to old stories. One of my all-time favorite books, Autobiography of Red, is a retelling of the Geryon myth. Another, Nox, is a “translation” of Catullus’s elegy for his brother.

This year, Maria Headley’s Beowulf stood out to me as a triumph. It’s probably not going to dethrone Carson’s retellings as a favorite, but it is a worthy and fun exploration of what it would really mean to bring Beowulf into the modern age.

4.

I hate playing favorites, but this is a year-end book list, so I should probably give you a run-down of some the books I found most notable.

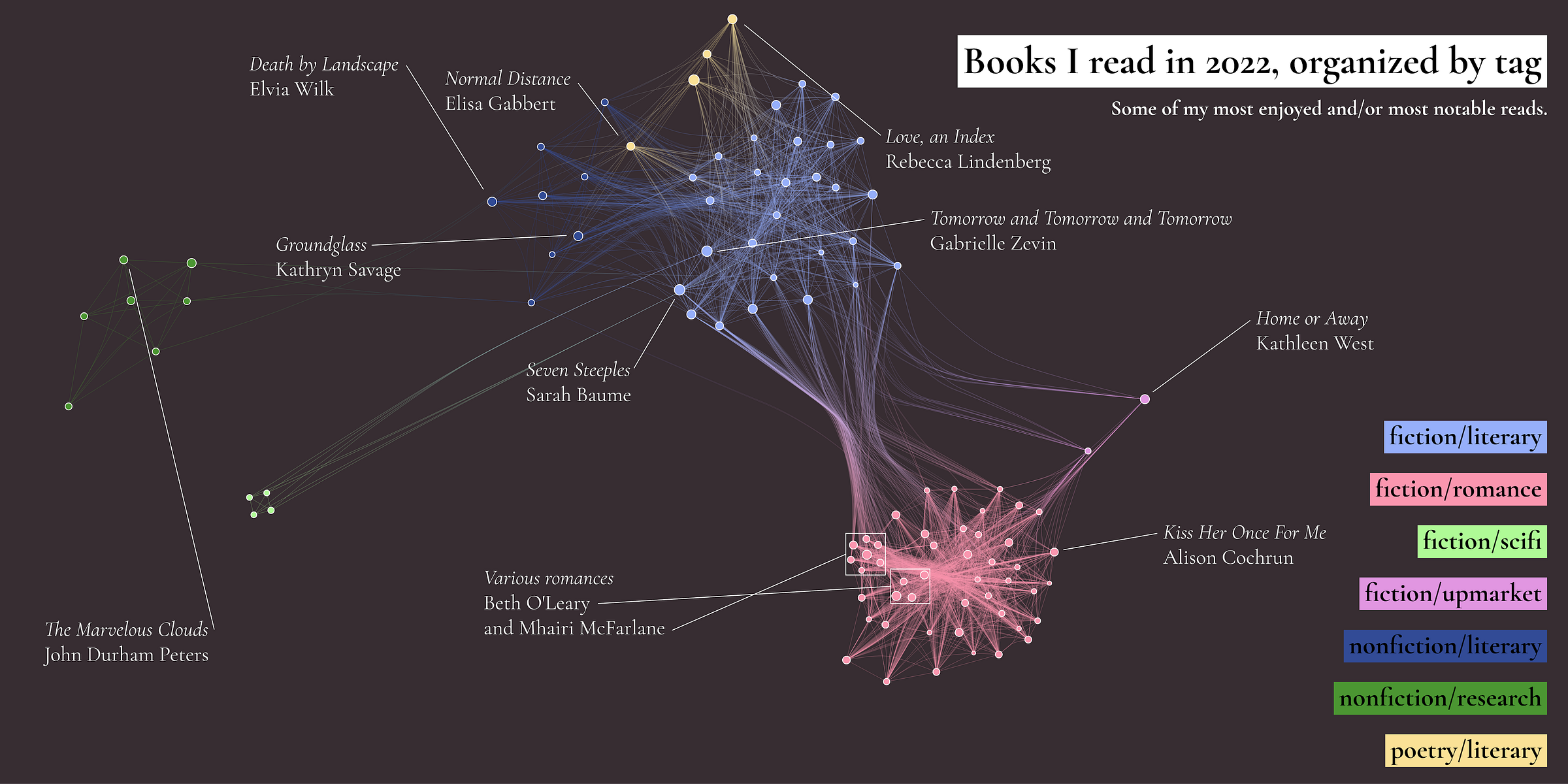

I highlighted books here that I found (1) deeply moving (see Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow, Seven Steeples or Love, an Index), (2) truly envelope-pushing (see Groundglass and Death by Landcape), (3) working perfectly within their forms (see The Marvelous Clouds, Normal Distance, Kiss Her Once For Me, or Home or Away), or (4) just a whole lot of fun (Beth O’Leary and Mhairi McFarlane).

Another thing that held these books together: they made me less afraid of the rising tide, the what, exactly, did you accomplish today? of it all. After Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow, I just sat there for almost twenty minutes, thinking about the book, about the world I had just inhabited. I didn’t, in that moment, see these books as a wall holding back the panic. The metaphor was different. These books were suits that let me swim beneath the waters of time, and see, just for a moment, that I’ve done enough.

This is great John! I used Wolfram to create a few graphs and networks for students to visualize books they read like the Great Gatsby but it's a cool idea to extend it to entire lists of books...I'm excited to check out some of your recommendations! If you are back in MPLS sometime look me up! Cheers-Matt (Westside soccer for life haha)